Acknowledgments

I’ll just add to the welcomes and acknowledgements that have already been made.

It’s such a special honour to have with us here today:

-

Wendy Taylor, President RSL South Eastern District and fellow veterans.

-

the CEO of Greenslopes Private Hospital Christine Went, whose work and team embodies the history of the hospital, an early part of which is set out in Prof Chris Strakosch’s Chapter. And whose hospital, following ‘the Ramsay Way’ does so much to support those broken veterans who most of us know not how to assist.

-

Irina Bruk, Honorary Consul General of Russia.

-

Captain Kasper Kuiper, former Dutch Honorary Consul and now Chairman of the Queensland Maritime Museum.

And I note a special apology from our great friend Dr David Cilento whose illness unfortunately prevents him from being with us today. David’s family home was on the corner of Villa Street and Ipswich Road abutting this park and much of this history to us, was to David his childhood reality.

And from Dr John O’Hagan AM CQA who turns 100 this year.

And to all of you, of course. Thank you. It’s so uplifting that you are here to support this important record of our place in this world.

An unwillingness to admit to shortcomings

Inherent in the military psyche is an unwillingness to admit shortcomings. This is an attribute in the heat of battle, and a blight in illness. (i)

For many, “seeking help, even admitting they have a problem, is thought to be a sign of weakness”. (1) A risk to career and promotion. (ii) And this extends across the divide of rank and station and, largely, profession.

And at its extreme, is illustrated in the horrific figures showing that almost 65,000 Australians per year attempt to take their own lives. (2) Picture the Gabba full (pre-Covid of course) then add another half again. It’s almost impossible to comprehend and might be debilitating if you could.

It is not just limited to the military, this blight. ‘Among male doctors the suicide rate is twice the rate of the wider male community. Among female doctors it is six times greater. (3)

Which links me back to where I began, veterans and hospitals and homes and helping and, now, having the discussion. Because we’re all in it together.

And so back to the book, Stephens and War.

It could equally be called Stephens at Home. It tells of Annerley and surrounding suburbs during war times and following. (4)

Challenging military history

Volumes like this place a mixed responsibility on the historian.

Military history and commemoration, is somewhat sacrosanct. (iii) To criticise it, (iv) or even question the entrance narrative (v) , or status quo (5) is, to many, commensurate with blasphemy for the religious. (6)

It has even been recorded that Charles Bean, WWI official historian, at one end of the spectrum “occasionally exercised a sanitising hand” while the more critical (and accurate) suggest Bean produced a distorted and misleading but “rather pristine image of the Australian soldier”. (7) Bean’s critics in the 1980s were pilloried. (8)

And some of the chapters of this book do show the unpleasant impacts of war on our community, but also shine a light on our most important role: Common endeavours to help each other. To provide:

-

supportive social relationships; family harmony;

-

a sense of control and purpose;

-

effective help-seeking; and

-

positive connections to good health services. (9)

All the things that help. And importantly here, to be able to tell the story.

A personal reflection

My own luck, was to have had as a boy and young man, a great mate, a friend of the family, a mentor or positive male role model you might call it these days, a doctor-come-gentleman-farmer.

Dr Tony Liggins had been a fighter pilot in WWII flying kitty hawks and spitfires against what he (and many of his ilk) called simply ‘the Japs’. (vi) I don’t think there was any personal malice intended, just a job to be done and a spirit of obligation we call patriotism. (10) He would often take me “up for a flip” in a little Cessna and amaze me with tales of derring do.

I spent many an hour listening to stories of Liggo’s escapades, told matter-of-fact, some with an element of fear, (vii) never boasting, (viii )…of flying sorties strafing villages, engaging in eye to eye combat in propeller driven aircraft, and all sorts of what would then have been comfortably couched as ‘boy’s-own-adventure’ type of stuff.

But nothing do I remember so clearly as his sitting with me, one spring afternoon, both of us sneezing, suffering from hay fever, as the sun set over Upsalls Creek, after a day cutting cattle and feeding the dog, after he had regaled me with another such war story, one where his wing-man, with whom he’d joined the Air Force, had been shot down.

I recall his reclining, overlooking the hills as if they, suffuse with his thoughts, told the story themselves, and he ‘you know Matt, these days, we’d have been pulled off duty, sent on leave to some sort of post-traumatic stress debriefing and spent a week in therapy’.

‘But instead’, he went on ‘we scratched some dinner around our plates, had a pretty poor night’s sleep getting savaged by mozzies and got up the next morning to fly another sortie. Nothing was said.’

Stephens and War – an overview

Nothing was said. It was an era where the prevailing attitude was ‘least said, sooner mended’.

And it is this sentiment that informs this book. Because these aren’t stories that glorify war. These are the stories that tell of what was required of people at home here in this local Stephens area during the war and in helping, on their return, those who we sent to do what we might not do ourselves.

You will be moved by Dr Walding’s account of the establishment of this remarkable Memorial Park, so that we do not forget the futility of war.

And of the Markey Boys, who both died serving in WWI, from a family who lived only 300m from this park. Imagine the grief, then exasperation, driven up to anger, that their parents and six sisters must have experienced at home (just over there) when their sons and brothers were not recognised on this Cenotaph or by a tree in Honour Avenue because they enlisted a mile and a half down the Ipswich Road at Buranda. You’ll have to read Daryl Soden’s chapter to see if there is

even a hint of a just ending to that one.

And of Jack Rigby, a 24yo local insurance clerk, who lived in Belfast Street at the other end of Honour Avenue, killed 10 hours after landing on the first day at Anzac Cove. And his brother George, shot in the leg and arm on the same day then lay overnight, wounded at Gallipoli.

Little wonder then, Jack’s daughter tells us in the chapter by Alan Tonks, he spoke very little about his wartime service.

In the first five days of being there, 600 of his colleagues were killed. And articles detailing the military camps in the area, by Peter Dunn OAM and the Annerley Drill Halls and local firing ranges by Mark Baker which also outlines the home and surrounds of the eponymous Stephens, in the vicinity of Junction Park State School.

Possibly most challenging, though, are Prof Michael Macklin’s terribly confronting accounts of our own war, between the First Nations people and European colonisers, right here, in what was described in 1825 as a ‘veritable garden of Eden’.

Equally confronting, of course, the accounts of courageous First Nation soldiers such as Fred Burnett, fighting alongside their colonisers. Colonisers who wouldn’t recognise them even to vote for half a century after their return. And while Rod Pratt poetically notes that “the overhanging branches of a nearby tree occasionally cover [his grave] with flowers” (11), Fred Burnett a Qld Aboriginal WWI veteran, to our collective shame, lays in an unmarked grave at Toowong Cemetery.

I implore you: read, reflect and act.

And there are stories of those who sought to repair our returning soldiers, at Greenslopes, at the Yeronga Military Hospital, Rhyndarra and of the adequacy, or otherwise, of the controls to protect local heritage places, written by Peter Marquis Kyle.

And of the programs to house our veterans and their families in war service homes and inter-war housing, to pull them together in RSL and community clubs when they returned broken and in need of care and, often, unwilling to tell their stories, or not knowing how to.

Nothing was said.

And so I hope, as well as being the fourth in a series recording the rich history of our area, this book reminds us of our duty, to remember if we, through our elected representatives, choose to send our sons and daughters off to do our dirty work for us, we must, when they return broken and deflated (or ten foot tall) (12), be equally obliged to look after them.

To realise that it is compassionate to allow those stories to be told, to acknowledge the pain and seek to repair the damage. To learn how to have those conversations, to care, so that something is said.

And so I say in closing,… “Look closer, there’s more here than war…what’s most inspiring is that in these [histories] last moments these [people] men were not thinking of themselves they were thinking of one another, and that’s love.” (13)

These papers remind us what is takes to make communities, like ours, so wonderful. And that’s love.

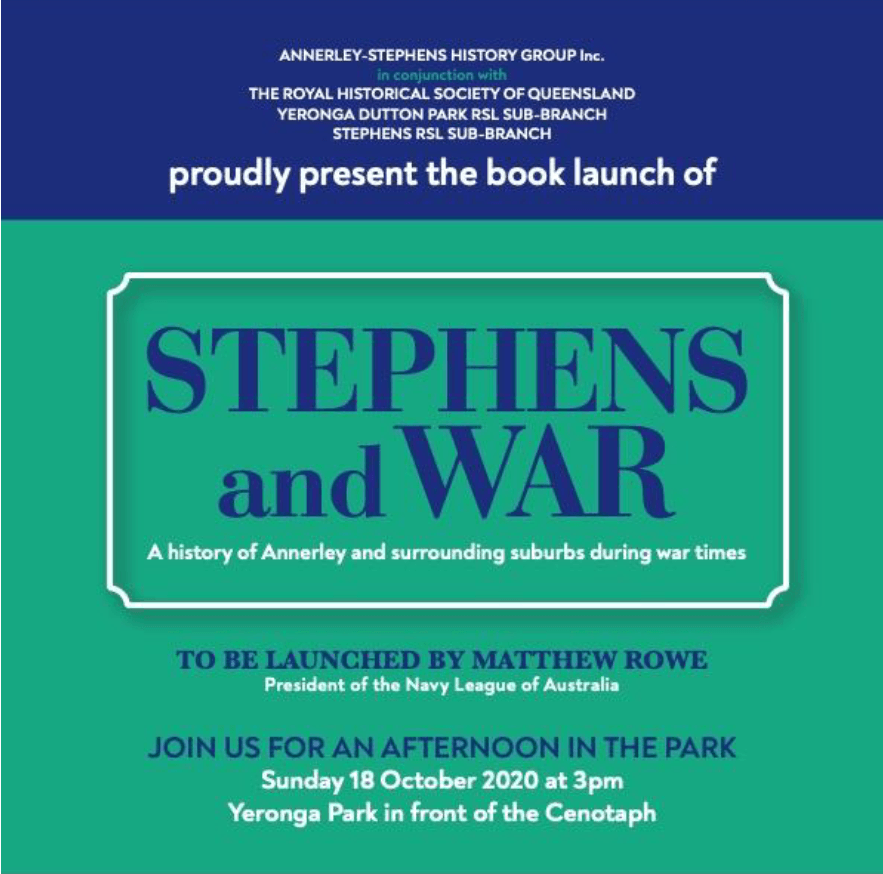

Book launch

So it is now my privilege, to officially launch the volume Stephens and War, and in doing so pay tribute not only to those who I have already commended, but importantly to:

-

Stephen Sheaffe AM, President of the Royal Historical Soc. of Q;

-

Dennis Peel, President of the Annerley Stephens History Group;

-

the conference speakers, authors and contributors.

I launch this book in the hope that by so doing we learn from the shortcomings, and great triumphs, of those who have gone before us. Remember…

The most fragile yet powerful of human emotions is hope … belief in a better future, a better world. Hope is sustained most by reaching out in support of one another… not letting one another down …[and remembering] what we need most is one another. (14)

And just as we remember, we look to the future, to the wonderful spirit of our caring for each other, with hope and compassion and joy.

In that spirit of progress, love and caring, I commend to you, Stephens and War.

- Jeff Kennett AC, Kennett: Insights & Reflections, Wilkinson Publishing, Melbourne 2017 p115

- Ibid, p29

- Black Dog Institute figures, personal email to author from Tony Stevenson, CEO Mental Illness Fellowship to

author of Australia of 15 October 2020 - Stephen W Sheaffe, AM, Stephens and War: A history of Annerley and surrounding suburbs during war times,

ASHG, Brisbane 2020 - https://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/museum-visitors-see-what-they-want-to-see/news-story/727d245a9646a7ceeeb13b89a2797600 accessed 10 Oct 2020

- Tom Frame, ANZAC DAY: Then & Now, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2016, p2

- David Kent, quoted in Frame, ibid, pp2-5

- Frame, op cit, p2

- Email from Tony Stevenson, CEO Mental Illness Fellowship of Australia to author of 15 October 2020

- Churchill said in 1940, referring to the Spitfire pilots, ‘never was so much owed by so many, to so few’.

- In Sheaffe, op cit, p25

- See for example https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/defence/ben-robertssmith-i-will-shoot-you-in-the-head-sas-at-war/news-story/b32c06b4c7a6ea2d81e0a5b2e9527143 accessed 10 October 2020

- Neil Oliver, the Scottish Archaeologist and historian. Quoted in Nelson, ‘Every nation has its story – this is ours’ address attended by author.

- Adapted from ‘From Fromelles to Pozieres – we remember’ T H E H O N . D R B R E N D A N N E L S O N A O National Press Club: Brendan Nelson Posted 20 July 2016 at 4:00 pm https://www.awm.gov.au/commemoration/speeches/Fromelles-Pozieres-we-remember accessed 9/11/2018.

(i) Nelson, H., P.O.W. Prisoners of War: Australians Under Nippon, 1985 ABC, p216, who wrote of Dr Ian Duncan, himself interred in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in 1945. He wrote:

At the end of the war I interviewed ever Australian and English solider in my camp… I thought it was my duty … And you’d say to them, what disease have you had as a prisoner of war? Oh, nothing much, Doc, nothing much at all. Did you have malaria? Oh yes, I had malaria. Did you have dysentery? Oh yes, I had dysentery. Did you have beriberi? Yes, I had beriberi. Did you have pellagra? Yes, I had pellagra, but nothing very much. [Of course] All these are lethal diseases. But that was the norm, you see, everyone had them. Therefore, they accepted them as normal.

(ii) In his book Exit Wounds former Major General John Cantwell AO DSC “told of his own battle with depressive illness and PTSD”, and of the systemic lack of support for him. “What chance [then] would a rank and file soldier [or sailor] have of accessing the appropriate support?” quoted in Jeff Kennett AC, Kennett: Insights & Reflections [insert ref] p18-19

(iii) See for example WWII Spitfire Pilot Ken Wilkinson of 19 Squadron, RAF interviewed in Spitfire: The Plane that Saved the World, Netflix documentary accessed 10 October 2020, who says “But the aura surrounding the Spitfire is more a post war phenomenon than a wartime thing … it was just an instrument of war then.”

(iv) Because the story Bean presented, while bloody and terrible, is closer to the Aussie ten-foot-tall bronze warrior legend than it is to some of the truths he uncovered. Much material rejected from Bean’s account, though in his files, later uncovered contains reference to cowardice, drunkenness, malingering, friction between the men…personal suffering, the waste of life and the dehumanising effects of warfare.” [See Kent, p4 of Tom Frame’s book ANZAC DAY: Then & Now [insert ref]

Bean’s file, but not his history, notes that:

Everyone who has seen a battle knows that soldiers do very often run away, soldiers, even Australian soldiers, have sometimes to be threatened with a revolver to make them go on … Then there is the nonsense about wounded soldiers wanting to get back from the hospital to the front…and …what here everyone knows – that it is not one soldier in fifty that wants to go back… They dread it…There is horror and beastliness and cowardice and treachery, over all of which the writer, anxious to please the public, has to throw his cloak… this is the true side of war – but I wonder if anyone would believe me outside the army. [Frame op cit p3.]

And when we question this, for many of us our entrance narrative, [see https://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/museum-visitors-see-what-they-want-to-see/news-

story/727d245a9646a7ceeeb13b89a2797600 accessed 10 Oct 2020] “critically and creatively thinking about the place of uniformed service and the importance of armed conflict in the evolution of the Australian nation” [Frame op cit p7] we place ourselves at risk “of being accused of lacking patriotic spirit” [Frame op cit p7], for many do not want to open that door.

(v) See for an interesting discussion on this subject: Smith, Professor Laurajane, Emotional Heritage: Visitor Engagement at Museums and Heritage Sites, quoted in https://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/museum-visitors-see-what-they-want-to-see/news-story/727d245a9646a7ceeeb13b89a2797600 accessed 10 Oct 2020 (from which the following quotes come)

In fact for many of us, events like today and other more military focussed commemorations, are an opportunity to reinforce our “entrance narratives”

“many of us don’t want to be challenged by what we see when we traipse through a museum or heritage centre. Instead we’re often unconsciously seeking affirmation of the stories we already know, the ones we carry into those exhibitions.”

Much evidence points to our ‘entrance narratives’ reinforcing our sense of self and our world views and knowledge rather than

“…many more tend to shrink away from that to preserve the emotional attachment they had to their entrance narrative.”

Many “tended to use the museum [and monuments] to reinforce their status quo”

(vi) Although some held such determined distaste, for example in my discussions with the late Cyril Gilbert OAM, himself an ex-POW, I learnt he refused to drink any beer made by the Japanese, causing much consternation for hosts (including at Government House Qld) especially as Castlemaine Perkins, brewer of his beverage of choice XXXX Bitter was purchased by Lion Nathan, a fully owned subsidiary of the Japanese Kirin empire

(vii) WWII Spitfire Pilot Allan Scott of 124 Squadron, RAF interviewed in Spitfire: The Plane that Saved the World, Netflix documentary accessed 10 October 2020 discussing his time in defence of Malta put it so well: “So we ended up with a dogfight anyway…at sea level… fighting for my life… A quick squirt [on the trigger]… you sweat profusely, and you’re not sweating because you’re hot, you’re sweating fear. And it trickles down your fore-head and in through from the eyes it trickles down into the mouth and its salty, and that’s fear. It’s a, a, salty taste.”

(viii) WWII Spitfire Pilot Allan Scott of 124 Squadron, RAF interviewed in Spitfire: The Plane that Saved the World, Netflix documentary accessed 10 October 2020 discussing his time in defence of Malta in describing a photograph showing the downed enemy Messerschmitt, points to the wrecked aircraft and says, sympathetically…] “….and there’s the poor old pilot there”.

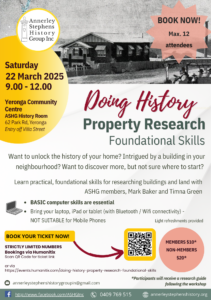

The papers delivered at the conference held on 26 October 2019 have now been published.

It is a high-quality publication of 225 pages with 20 chapters. All the papers delivered at the conference plus others are included. The topics of each of the chapters are noted below.

$25.00 per volume:

Please ring to collect or arrange for delivery

Deposit: ASHG: Westpac, BSB 034-033: ACC 30-9907

Please contact:

- ASHG: [email protected]

- ASHG Convener: Stephen Sheaffe: 041 777 0176: [email protected]

- Stephens RSL: Matthew Rowe: 0418 797 597: [email protected]

- Yeronga Dutton Park RSL: Gavin White: 07 3848 8299: [email protected]

These are an eclectic collection of articles about war within the boundaries of the old

Stephens Shire

The speakers and topics are:

1. Yeronga Park: Dr Richard Walding

2. Fred Burnett, a Queensland Aboriginal soldier in the First AIF: Rod Pratt

3. Military Camps in the Stephens Shire area during WWII: Peter Dunn OAM

4. Rhyndarra, Yeronga Military Hospital: a conservation bungle: Peter Marquis-Kyle

5. Local History Beyond Appearance: Dr Neville Buch

6. The Military Hospital at Greenslopes in World War Two: Prof Chris Strakosch

7. War Service Homes: Dr Carmel Black

8. History of the Stephens RSL Sub-Branch: Matthew Rowe

9. Short History of the Yeronga-Dutton Park RSL Sub-Branch: Ross Wiseman AM

10. Early History of the Yeronga-Dutton Park RSL Site: Dr. Michael Macklin

11. Interwar Housing at the Four Mile Swamp: Kate Dyson

12. The Annerley Drill Halls on Portion 105: Mark Baker

13. Tom and Jack: The Markey Boys: Darryl Soden

14. They shall not grow old: The Neil family and two military disasters: Marjorie Neil

15. The Rigby family during the First World War: Allan Tonks

16. Finding the First War Service Home in Queensland: Denis Peel and Kate Dyson

17. Wartime History of Kathleen Morris Paddock: Claire Mitchell

18. 2019 ANZAC Day address at Yeronga Park: Stephen Sheaffe AM

19. Stephens RSL Remembrance Day Centenary Walk address, Matthew Rowe

20. Annexures: Stephen Sheaffe AM

Annexure A: A brief history of Yeronga Memorial Park from 1879 until WWI

Annexure B: A brief history of the Stephens Shire

Annexure C: Population of the Stephens Shire

Annexure D: Names of soldiers on the Cenotaph.