Kookaburra on back deck, 9 Inchcape Street, Fairfield, 2019

Every morning in Inchcape Street, Fairfield we wake up to a symphony of bird voices. It changes throughout the year depending on what is flowering and fruiting but it also changes from year to year. Long term residents recall a period when sparrows and pigeons were the most common species with few if any honeyeaters, lorikeets, and noisy miners that are so prevalent now.

History is normally reported from the point of view of humankind, that is, how the passage of time has affected the human population. This paper aims to look at the changes that have occurred in the inner Brisbane city suburb of Fairfield in the last 200 years and speculate how those changes may have affected the population of birds.

By using historical accounts, maps, plans, photos and paintings the environment of Fairfield will be analysed at three, one-hundred year intervals, i.e. 1820, 1920, and 2020. For each of these times the major types of habitats extant for birds will be conjectured and the species of birds likely to be found in those habitats discussed. Some current recording and past anecdotal observations of birds will aid the discussion that this paper aims to encourage.

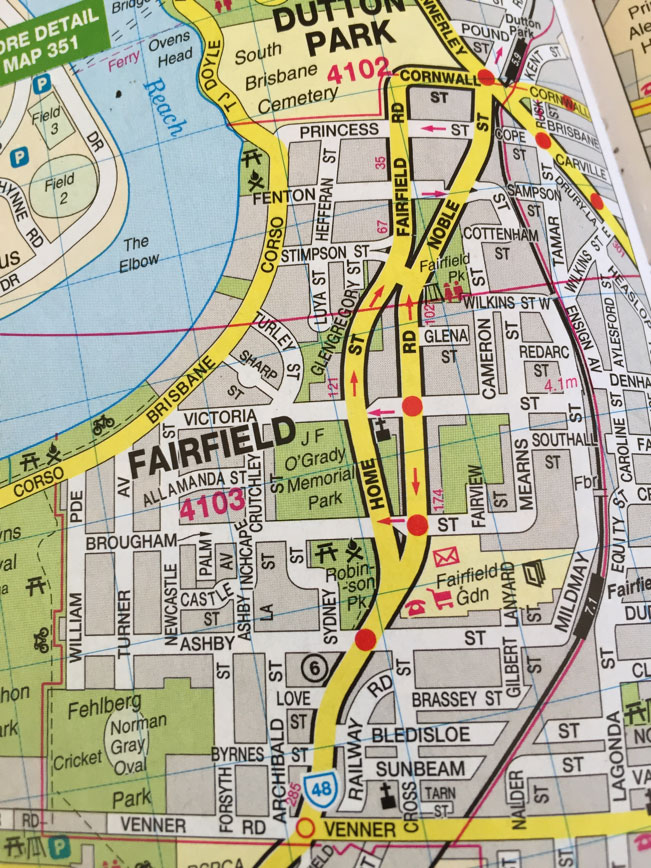

Fairfield 2020

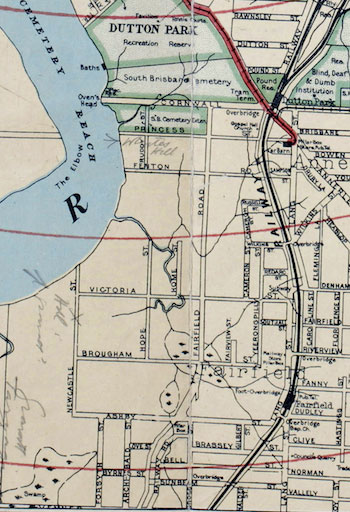

Fairfield 1924 (from Brisbane Centenary Official Historical Map)

Fairfield

Fairfield is a small suburb about 4.5 kilometres south of the city centre of Brisbane. The present suburban boundaries are Maiwar (the Brisbane River) to the west, the South Coast railway line to the east, South Brisbane Cemetery to the north, and Venner Road to the south. These boundaries aren’t important for any observers of birds so they aren’t strictly adhered to in the discussion that follows.

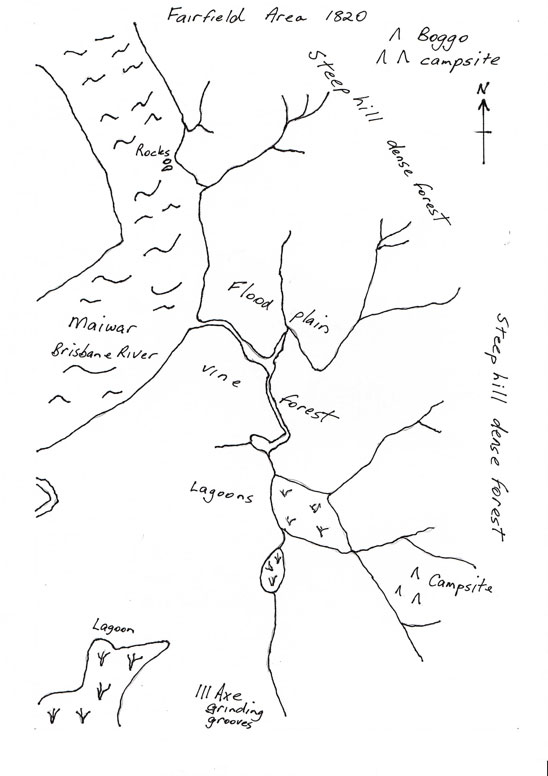

Fairfield in 1820 – home to the Yerongpan clan of the Chepara people

“ In a few small areas along the Brisbane River – around West End; from the southern end of Dutton Park to Fairfield … the vista was broken with ‘luxuriant vegetation’ – pockets of vine forest and wet schlerophyll/rainforest. Ferns, orchids, staghorns, figs (with edible fruit), bloodwood, mahogany and hoop pines were reported in these areas…

The Boggo Road/Fairfield area had another set (of campsites), on the borders of the former ‘Boggo Scrub’ (vine forest that was presumably important towrie (1) ) … On the other side of the Boggo Scrub lay a camp in the vicinity of Fairfield Railway Station, not too far from the ‘Fairfield’ axe grinding grooves (at 153 Venner Road).” (2)

Fairfield axe-grinding grooves 2016

The river bank in 1820 would have looked very different to today with the tall forest and thick scrub extending on to it. There were probably no mangroves to be seen as the river water at this point was too fresh for their survival (3). It was only the removal of the sand bar at the river entrance and the much later dredging further upstream that enabled the spread of mangroves to Fairfield. (4)

Fairfield is part of the flood plain of Maiwar (Brisbane River) and apart from regular inundations there were permanent wetland areas in the vicinity of Robinson Park, Norm Rose Park, Fehlberg Park and Fairfield Park. For the Yerongpan people the lagoons provided turtles and eels and edible plant food.

The area around Fairfield Station extending up to the axe grinding grooves in Venner Road was most likely a reasonable clearing in the scrub allowing for regular periods of dwelling. It is likely that controlled burning would have been practiced to at least maintain this campsite and the pathways through the scrub.

Bird habitats & likely bird species in 1820

- The River. A much shallower river to the depth at present with more exposed rocks and sandbars could have supported the birds that are predators of fish and other marine foods e.g. pelican, heron, egret, brahminy kite, sea eagle, darter, cormorant and duck as well as insect eaters like welcome swallow and rainbow bee-eater. For the Chepara people “Water birds were also favoured foods. The black swans or marutchi which were often seen on the River were easily caught during the moulting season.” (5)

- Forest. The tall trees and thick scrub might have been similar to some of the areas of Brisbane Forest Park or Toohey Forest that support seed and fruit eaters like lorikeet, cockatoo, and corella. Tall trees could have also been home to kookaburra, tawny frogmouth, Southern boobook, brown goshawk and powerful owl. The understory could have harboured Eastern whipbird, fairy-wren, robin, white-browed scrubwren and honeyeaters.

- Wetland. Oxley Creek Common is probably the nearest surviving similar area. Birds found around this type of wetland are aquatic birds like duck, grebe, swamphen, crake and coot and waders like spoonbill, heron, and egret. The fringes of wetland could be home to masked lapwing (commonly called plover), stone curlew, tawny grass birds and golden-headed cisticolas.

Pelican photo: Susan Chisholm, April 2020, Maiwar

4. Campsite. This environment may have not been too dissimilar to a 2020 backyard and could have featured butcher bird, magpie, magpie-lark (peewee), crow, willie wagtail as well as visitors from the forest birds above.

Fairfield in 1920 – farms, houses, railway, roads and draining swamps

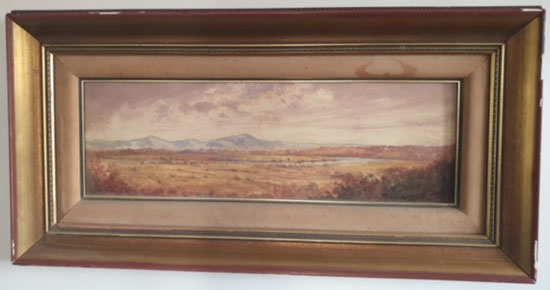

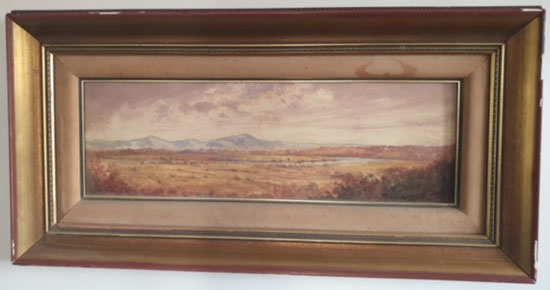

George Wishart 1916

George Wishart painted a picture in 1916 which views the Fairfield plain from a vantage point near the corner of Clive and Hastings Streets, Annerley. It shows a small cluster of houses surrounded by tilled fields that extend right up to the riverbank. In the centre of the painting the river sweeps round “The Elbow” of St Lucia into the Dutton Park reach and three foothills of the D’Aguilar Range are recognizable landmarks in the background as is the ridge on the right that carries Dornoch Terrace down from Highgate Hill to Hill End.

Much of the clearing of the forest had been done between 1860 and 1880 by Joseph Thompson (Thompson Estate was named after him) who shipped 40 000 pine shingles to Melbourne (6). The Grimes brothers had very successfully farmed a lot of the area growing maize, arrowroot, sorghum, lucerne, and vegetables from 1860 onward. Dairy farming was still significant in the 1920s with Stimpson, Wellauer and Hubner among some of the predominantly Germanic dairy farmers. (7)

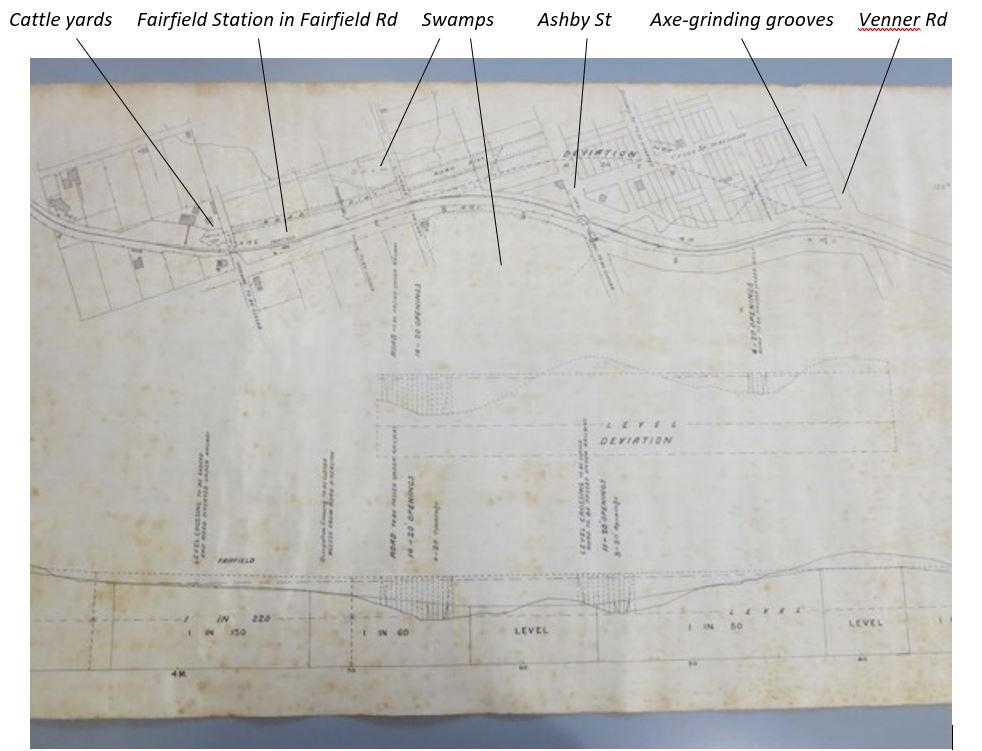

1891 railway map (Queensland State Archives)

A map was drawn in 1891 after a flood that prompted the rerouting of the rail line from its original path along Fairfield Road. After the much more significant 1893 floods the planned deviation was dropped in favour of moving further up the hill towards Annerley. The 1891 map shows the old position of Fairfield Station which was just a siding for loading produce in Fairfield Road, near Victoria Street with cattle yards handy in Victoria Street. (L C Hair and Beauty Salon would have been neighbours). There are two swamps marked which are in the areas of Robinson Park and Norm Rose Park (this one extends into what is now Fairfield Gardens carpark) and a watercourse is shown running from the Ashby Street/Fairfield Road corner back up towards Venner Road. The end point of this waterway is adjacent to the position of the axe-grinding grooves which would have made use of this water supply. Earlier maps also show the Fehlberg Park swamp which was deemed a “Reserve for Access to Water”.

So, by 1920 although the forest had been cleared for farming much of the wetland was still remaining.

Bird habitats & likely bird species in 1920

- The River. Without the cover that had been provided by the forest extending to the riverbank, some bird species would have reduced in numbers and/or moved elsewhere while the fish hunting birds, welcome swallows and rainbow bee-eaters might have not been too disrupted from their normal routines.

- Pasture and crops. This is the biggest change with the open paddock areas meaning that the forest birds lost their sources of food and locations for nest building and protection. Some species that are seen in this type of habitat are crow, magpie, kookaburra, sacred kingfisher, finches and raptors such as the brown goshawk and kite varieties. Sparrows and starlings were introduced to Australia during the mid 1800’s and were soon seen as pests destroying farmer’s crops and spreading disease. By 1920 the Flying Fox and Crow Destruction Board was paying bounties on flying foxes, crows, scrub magpies, as well as sparrows, starlings and their eggs. (8)

- Swamps. The wetland birds are now in much closer proximity to humans and traffic, causing disruption, but a significant amount of this habitat is still intact. Numbers may have reduced but some habitat was still there for the wetland birds.

- Backyards. In the style of the 1920s these were commonly mostly open grass areas with vegetable and flower gardens and the occasional fruit tree. The introduced birds like feral pigeon and sparrow colonized these areas along with magpie, magpie-lark, butcher bird and willie wagtail. There were extra introduced hazards for birds in backyards in the form of lethal predators – domestic cats and dogs.

Tawny frogmouths, South Brisbane Cemetery: Susan Chisholm 2019

Bush stone-curlew: Jennie O’Brien Lutton Jan 2020, median strip, Fairfield Road

Fairfield in 2020 – Suburbia, parks and backyards.

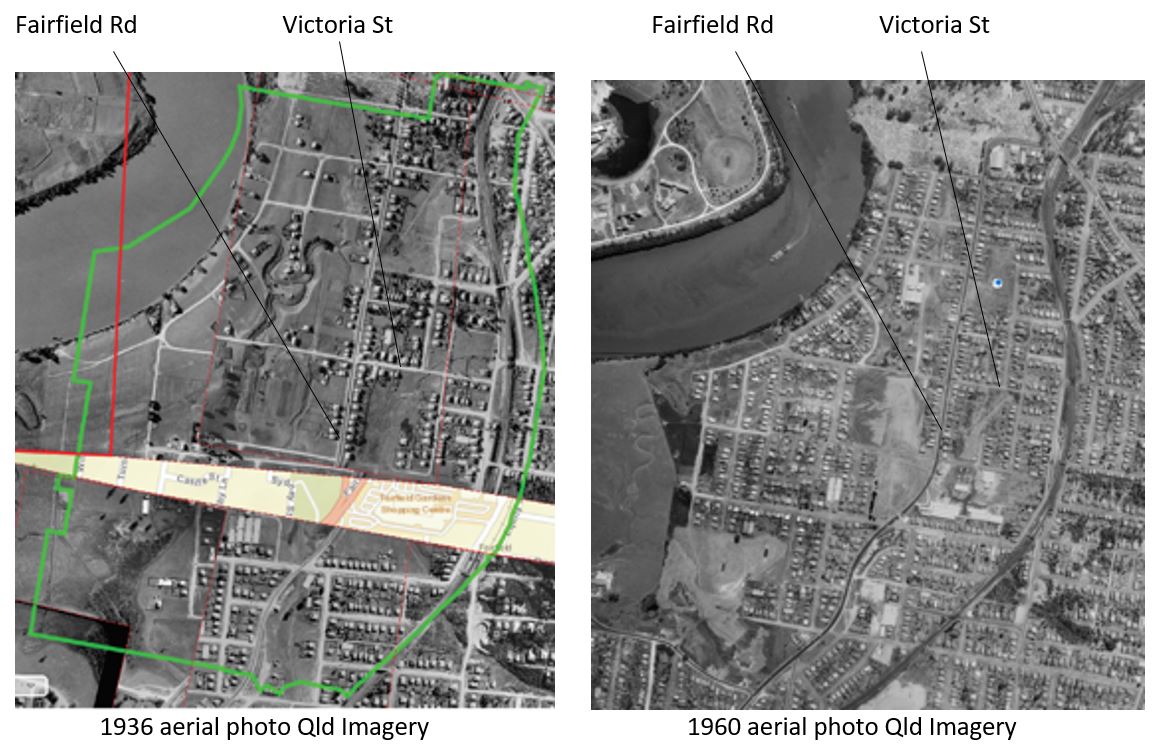

After 1920 the wetlands of Fairfield began to disappear, being drained then infilled as garbage dumps and then, finally, top dressed and turned into parks. Over the next 30 years all the wetland was replaced by open grassy areas with avenues of planted trees including jacaranda and fig trees. A 1936 aerial photo shows the drained watercourses and swamps with housing mostly along Fairfield Road and near to the train station and on the higher land. The flood plain was still largely being used for agriculture.

After World War 2 the population boom placed pressure on this area close to the city and farming completely gave way to the development of housing. The 1960 aerial photo shows a housing footprint that has been fairly consistent over the next 60 years. The Tickles warehouse occupies the Fairfield Gardens shopping centre site and the Luya Julius sheds can be seen on the eastern side of Luya Street. Backyards and parks in 1960 appear very open with few sizeable trees.

From the late 1960s the Brisbane City Council began planting trees along some suburban street footpaths and in the Fairfield parks, there was also encouragement for residents to plant mostly native trees. The rate of planting escalated through the 1970s mainly in a bid to make Brisbane prettier for the 1982 Commonwealth Games (9). The 1991 aerial photo shows some of these trees have grown into sizeable specimens. The riverbank is covered by a thin band of mangroves as the dredging of the river has made this bend of the river much more salty. Fairfield Gardens has replaced the Tickles factory.

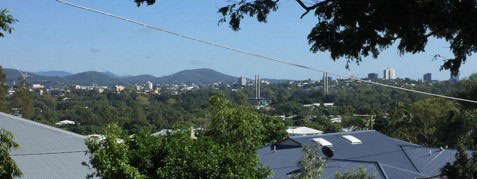

The full extent of the “greening of Fairfield” can be seen by comparing a photo taken in 2020 from the same spot in Hastings Street, Annerley on which George Wishart’s created his 1916 painting. The three hills in the background confirm that these two scenes are of the same piece of country. The pylons of the Eleanor Schonell Bridge in the photo mark the position of the river that is almost completely hidden by foliage and the iconic “Torbreck” apartment block marks the high point of the Dornoch Terrace ridge. The angle and elevation of this viewpoint gives the impression that Fairfield has returned to partly at least a forest habitat.

Over the last 200 years the clearing of the Boggo Scrub for farming, the draining of the wetlands, the creation of suburbia, and finally the “greening” of parks and backyards has changed the habitats available for birds.

Bird habitats & likely bird species in 2020

- The River and mangrove strip. The riverbank now provides more cover with the migration of mangroves up river. An understory has developed along the bank in some places. Most river bird species from the past two hundred years are still resident with striated heron observed breeding in the mangroves in 2020 (10). Some of the species seen and heard on occasion in the mangroves and in the understory have been spangled drongo, fairy-wren, rainbow bee-eater, whipbird, brush turkey and pheasant coucal.

- Backyards. The food and shelter provided by the planting of native (and other) trees has seen a changing of the guard in backyards with the return of honeyeater, noisy miner, lorikeet, cockatoo, butcherbird (both pied and grey), kookaburra, tawny frogmouth and Southern boobook.

- Parks. While wetland has disappeared some birds common to areas around wetland can still be seen in parks in Fairfield. Notably masked lapwing and Australian white ibis. Often cockatoo, corella, and galah can be seen feeding on grass seeds and bush stone-curlews can be seen and heard at night. Brown goshawks are quite common now and were observed nesting in South Brisbane Cemetery in 2019 (11).

Striated heron chick: Rae Clark, May 2020

Continual change

Every environment is continually changing and also feels the effects of changes in conditions in other environments. The drought of the last decade has affected conditions across the continent and so birds have done what comes naturally and gone in search of finding more hospitable places to visit and live. Recently the spectacular scarlet honeyeater and an Eastern spinebill have been spotted feeding in some backyard trees (12). The increase in numbers of cockatoos and lorikeets, for example, can also be connected with loss of habitat in other areas due to land clearing and bushfires. The rapid growth in Australian white ibis (sacred ibis) numbers has also been put down to the loss of wetland habitat along the Murray-Darling system. (13)

The bush stone-curlews that can often be seen standing around the shrubs and trees in the Fairfield Gardens carpark or on the median strip in the middle of busy Fairfield Road are an amazing story of survival and adjustment to urbanization. These birds along with the riverine birds like pelican and heron, raptors like the brown goshawk and perching birds like magpie, crow, kookaburra and white-browed scrubwren have probably been continually present in Fairfield for 200 years (and well beyond that).

Some of the bird species that inhabited the forest of the Boggo Scrub disappeared as the land was cleared but returned in the later part of the twentieth century, like honeyeater and lorikeet but some species have not returned, tree creeper and robins are in this category.

The invading species like sparrow and common myna thrived in the early to mid-twentieth century but have reduced in numbers with the “greening of Fairfield” and return of the competing native birds.

We are fortunate to live so close to the heart of the city and still be awoken each morning with the dawn chorus of so many different bird varieties.

Scarlet honeyeater, Fenton Street: Susan Chisholm

* Denis Peel is an amateur local historian and even more amateur bird enthusiast who lives in Fairfield. Much assistance has been given by Rae Clark, Susan Chisholm and David MacDonald who are avid local birdwatchers.

(1) Towrie is a food gathering area

(2) Ray Kerkhove Indigenous Aboriginal sites of Southside Brisbane https://mappingbrisbanehistory.com.au/brisbane-history-essays/brisbane-southside-history/first-australians-and-original-landscape/indigenous-sites/

(3) Although the rise and fall of the tide in this area can be up to two meters, the fresh water flowing down the river floats on the incoming salt water.

(4) Historical changes of the lower Brisbane River – Moreton Bay Foundation.pdf, Jonathon Richards 2019

(5) Helen Gregory The Brisbane River Story p 10 Aust Marine Conservation Society 1996

(6) Annie Mackenzie Memories Along the Boggo Track p 15 Boolarong Publications 1992

(7) Christopher Dawson Fairfield p 11 Inside History 2010

(8) The Stephens Shire Council was represented on The South Coast Crows and Flying Foxes Destruction Board by F A Stimpson and in 1916 the council opposed the inclusion of the “scrub magpie” on the list of pests to be destroyed. The Brisbane Courier 15 Mar 1916, p8. Stimpson wasn’t successful as magpies continued to be hunted and in 1925 the Brisbane and District Crows and Flying Foxes Destruction Board reported the numbers of pests destroyed in the preceding year were: Flying foxes 42 062, crows 3457, scrub magpies 2149, sparrows 50 789, sparrows eggs 21 412, starlings 5258, and starling eggs 100. The Daily Mail 31 Jan 1925, p8. The South Coast Crows and Flying Foxes Destruction Board was succeeded by the Brisbane and East Moreton Pests Destruction Board which operated from 1925 to 1961. The bounty on pests operated from at least as early as 1915 until the 1950s or beyond.

(9) From a conversation between the author and former Brisbane City Councillor and Lord Mayor Tim Quinn

(10) Observed by Rae Clark and others May 2020

(11) Observed by Rae Clark 2019

(12) Observed by David McDonald and Susan Chisholm 2019/20

(13) Wild About Ibis Dept of Environment, NSW Government https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/nature/wildAboutIbis.pdf